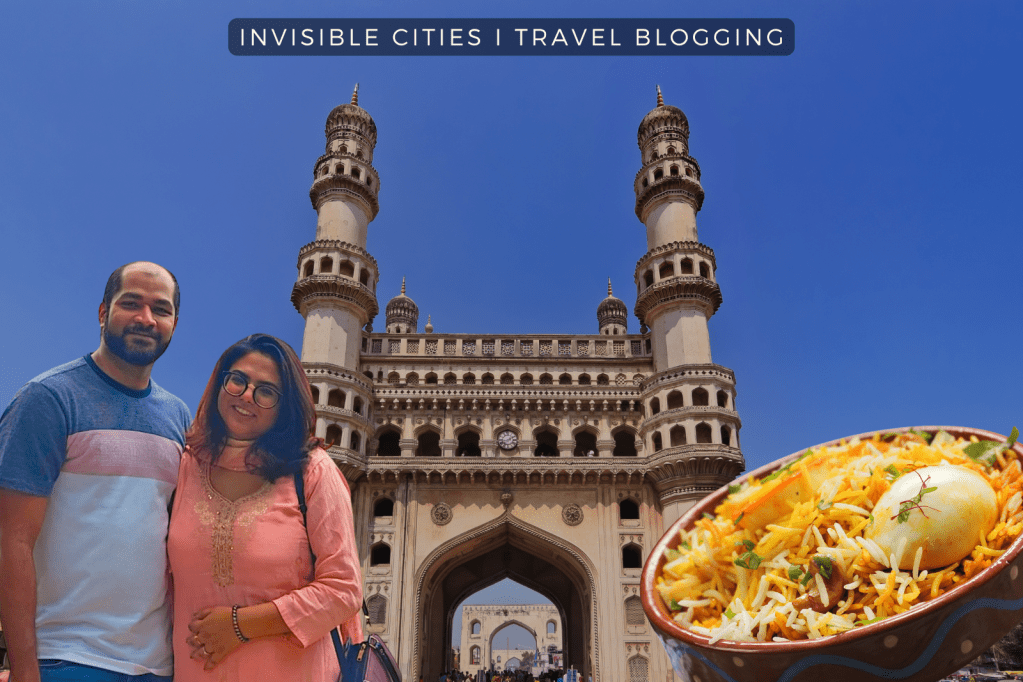

Our first few days in Sikkim felt slow in a way we hadn’t expected. Distances looked short on maps, but the road had its own rhythm. What I mean is – the pauses for landslides, stops for tea, long stretches where the majestic views demanded silence.

Of course, the non-mountain people will say –“oh! It’s the same in every mountain”, but trust me, it’s not. If you look closely, Even geographically, that’s not right. Bleh!

What we felt is that, somewhere between Gangtok and the quieter villages beyond, we began to notice diverse patterns. Basically not dramatic differences, but small repetitions.

For example, the same food appears in different homes. The same prayer flags outside places of worship that weren’t always Buddhist. Conversations shifting languages without anyone drawing attention to it.

Sikkim, we realised, doesn’t explain its diversity upfront. It lets you arrive at it gradually, as you traverse through the state.

I mean, how serene is that! Allow me to walk you through it.

Lepcha Community in Sikkim: Beginning with the Landscape

Historically, the Lepchas are recognised as the earliest known inhabitants of Sikkim and the surrounding eastern Himalayan region. This includes parts of current-day North Bengal and western Bhutan. Yes, we read this on Wikipedia, duh!

With that history in mind, traveling through Sikkim makes certain details easier to notice. Like, one can observe how the people treat nature. Some stretches of land remain untouched. Rivers are approached with a pious attitude.

Traveling alongside the Teesta River, we noticed how often people stopped near it. Sometimes to wash their hands, sometimes just to stand quietly. That’s a calm moment you usually don’t come across near the Ganges in the metro cities.

Later, our driver dada mentioned that many Lepcha families still see rivers as a living presence rather than sole utility. What a lovely thing to practice!

This way of relating to the land predates modern Sikkim.

Long before the region became a kingdom, the Lepchas lived here with belief systems rooted in nature and balance. Even today, their influence is evident in the state’s strong environmental awareness. The state is also reluctant to push tourism beyond certain limits.

As travellers, it was something we felt and experienced very closely. The very sense that the land was not just scenery, but a participant at will.

Now, as we climbed higher, it was time to meet the Bhutia community.

Bhutia Community and Tibetan Buddhism in Sikkim

As the road elevated, the landscape changed (Ofcourse) and so did its markers.

Prayer flags began appearing more often, strung across bridges and roads. Monasteries sat steadily on ridges, visible yet never demanding.

And I learnt from my nerdy husband that this was where the influence of the Bhutia community started.

He narrated that the Bhutias migrated from Tibet between the 14th and 17th centuries. They brought with them Mahayana Buddhism, monastic traditions, and systems of governance.

Uff, nerd!

Next up, at Rumtek Monastery, we spent time walking along the exterior. Fathoming at the architecture rather than focusing on rituals. The Locals moved through the space as if it was an involuntary action for them. Some were praying, some sitting by themselves, and others just passing through.

Honestly, for me, what stood out, even while travelling, was how this shift didn’t displace existing beliefs. The Lepcha traditions continued alongside Buddhist practices, often blending rather than competing.

The coexistence was voluntarily practiced. Diversity won in Sikkim.

And talking about coexistence, let me tell you how that shaped up. Read along.

How Coexistence Took Shape: Kabi Lungchok and an Early Agreement

This coexistence became easier to understand after visiting Kabi Lungchok.

Set within a quiet forested area, the site marks where the Treaty of Blood Brotherhood was established. It was between the Lepcha chief Thekong Tek and the Bhutia leader Khye Bumsa. The agreement formalised friendship, mutual respect, and shared responsibility over the land.

We entered Kabi Lungchok with the high hope of a grand set up. But honestly, it was just the opposite. No elaborate structures, no crowd. The simplicity of the space makes the history feel so much closer and real. The silence makes you think about it and question culture in a curious manner, rather than accepting what was evident.

How uncommon and real is that, tell me?

As we read on the boards, this treaty laid the foundation for Sikkim’s political and cultural structure. It established a precedent for governance through agreement rather than force.

An approach that would later influence how new communities were integrated into the state. Standing there, it felt like encountering the origin of a shared understanding. How beautiful!

The Arrival of the Nepali Community in Sikkim

I have a close friend and colleague from Nepal and was particularly interested in this part. So, the arrival of the Nepali community in Sikkim, began largely in the 19th century. It was encouraged by the monarchy to support agriculture and settlement.

And we could see that reflect in our journey. The car kept climbing through areas near Ravangla and Namchi. And the terraced fields offered a proud record of this history.

These terraced hills were shaped over time, through repeated labour and familiarity.

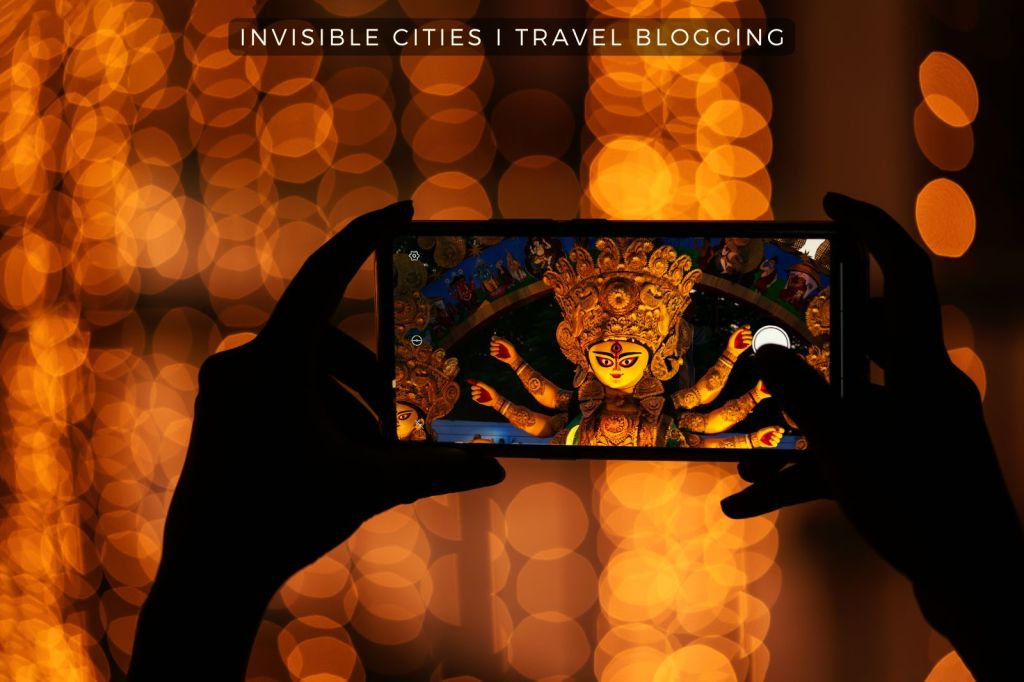

The Nepali community brought agricultural knowledge, food traditions, and a blend of Hindu and Buddhist practices.

Talking to some locals at a chai shop, we came to know that the festivals such as Dasain and Tihar became part of Sikkim’s shared calendar. All thanks to the Nepali community.

Now, it is celebrated across communities rather than confined to one. True to its diversity, really!

Oh wait, here’s an add on. The language here is adapted as well.

Nepali emerged as the most widely spoken language in the state. It is often used alongside English and regional dialects.

So what happened is that, rather than replacing older languages, it functioned as a connector, easing communication across communities. And again, what’s notable is how these additions did not overwrite existing systems. They settled into them.

“Adapt” should be the keyword of this state. Really!

Sikkimese Food Culture: What We Ate Along the Way

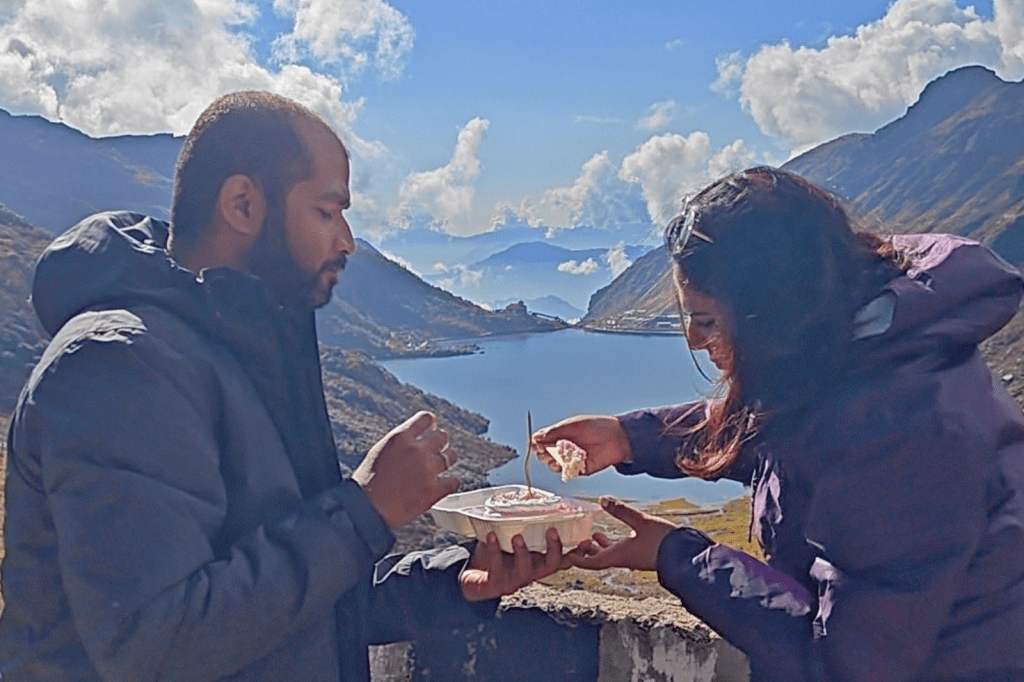

Okay, my favourity topic here!

Food became one of the most relevant ways to see how cultures in Sikkim overlap. Here’s how:

For lunch, we often ate Nepali thalis.

It included rice, lentils, vegetables, pickles. This felt practical rather than ceremonial, shaped by terrain and routine. And over time it became clear how deeply this style of eating has settled into everyday life across communities.

Also, the dinners often included tingmo. It is the soft Tibetan steamed bread served with warm gravies. Meals were usually shared, and the food was placed at the centre. We all passed it around without much thought. Thus, reinforcing how eating here is often a collective act.

Oh wait, I almost forgot. We also tried tongba.

It is a fermented millet drink served warm, common in colder regions. It’s slow by nature. You sip, refill with hot water, wait, and talk. The drink itself creates a pause, encouraging people to sit longer and move gently through the evening.

How social is that? Now that’s what you call – social drinking!

Also, do you see? How little the food belonged to any single community.

Sikkimese cuisine reflects years of shared kitchens, borrowed recipes, and gradual adaptation. Phenomenal!

What Connects It All?

As we moved from one place to another, the same patterns kept appearing. Like shared spaces, overlapping traditions, quiet agreements that continued long after they were made.

In conclusion, Sikkim doesn’t frame unity as an idea to be understood. It appears in how people move through land, through food, through public life.

By the time we left, these connections felt less like observations and more like context.

Something that explained the state without needing to define it.

Till then, happy reading!

Leave a comment